Varlink for Java is a Java based implementation of the Varlink interface. This blog post shows how varlink can be used in the Java world to solve the problem of accessing operating system functionality.

Consuming operating system functionality from Java, when running on Linux, has always been a problem. There are numerous examples where people fork processes and parse the result in ways which tend to break the next time you upgrade your CLI tools. Not even thinking about switching to a different version of your favorite Linux distribution or switching to another distribution at all. Of course there have been all kinds of approaches to solve this like JNI, DBus, … Then again, the operating system is way more than the kernel and the desktop. Configuring a network time server, installing additional packages, reading the system log, … And of course in a polyglot world, all this is not necessarily exposed using a C based API.

Over the time, and thanks to Harald, I have been following the Varlink project. You can also read more about this in his recent blog post about varlink. Varlink defines itself as:

… is an interface description format and protocol that aims to make services accessible to both humans and machines in the simplest feasible way.

So let’s put that claim to a test. :-)

Quick overview

Varlink uses a socket based, client/server based approach to communicate. It support TCP but also Unix domain sockets (UDS). Although the latter is still not officially supported in Java, Netty offers a neat solution and also allows you to use the same networking API with TCP and UDS. Still, let’s go the extra mile and use UDS for this.

The protocol for communicating between client and server is rather simple. The client issues a call and waits for the result. All communication is zero-byte terminated strings, which happen to be JSON. I won’t dive into the protocol any further, it really is that simple and you can read about it at the Varlink protocol documentation anyway.

As Netty does most of the networking, GSON takes care of the JSON processing, so we can focus on the actual API we want to have. For this let’s have a closer looks at how Varlink works.

Varlink offers services aka “interfaces” to expose their functionality. Every interface does also export information about itself. Varlink interfaces actually run in different processes (or even in the Linux kernel) and do expose their functionality over different addresses (e.g. unix domain sockets or TCP addresses). Therefore a default (well known) service of Varlink is the “resolver”, which allows to you to register your service with, so that others will be able to find you. As a first step I decided to focus on the client side, consuming APIs rather then publishing them. So the steps required are simply:

- Contact the resolver

- Ask for the address of the required service

- Contact the resolved address

- Perform the actual operation

Of course talking to the resolver is using the same functionality as talking to other interfaces, as the resolver is a varlink interface itself.

A simple test

After around two to three hours I came up with the following API, contacting the varlink interface io.systemd.network, querying all the existing network interfaces of the system:

try (Varlink v = varlink()) {

// shorter & sync way

List<Netdev> devices1 = v

.resolveSync(Network.class)

.sync()

.list();

dump(devices1);

// more explicit & async way

List<Netdev> devices2 = v

.resolver()

.async()

.resolve(Network.class)

.thenCompose(network -> network.async().list())

.get();

dump(devices2);

}

To be honest, for this specific task, I could have also used the Java NetworkInterface API. But the same way I am querying the network interfaces with varlink, I could also access the io.systemd.journal interface or org.kernel.kmod and interface with the system log or the kernel module system.

Just for comparison you can have a look at the Eclipse Kura USB modem functionality, which needs to call a bunch of command line utilities, access lock files, call into JNI code, …

The IDL – Xtext awesomeness

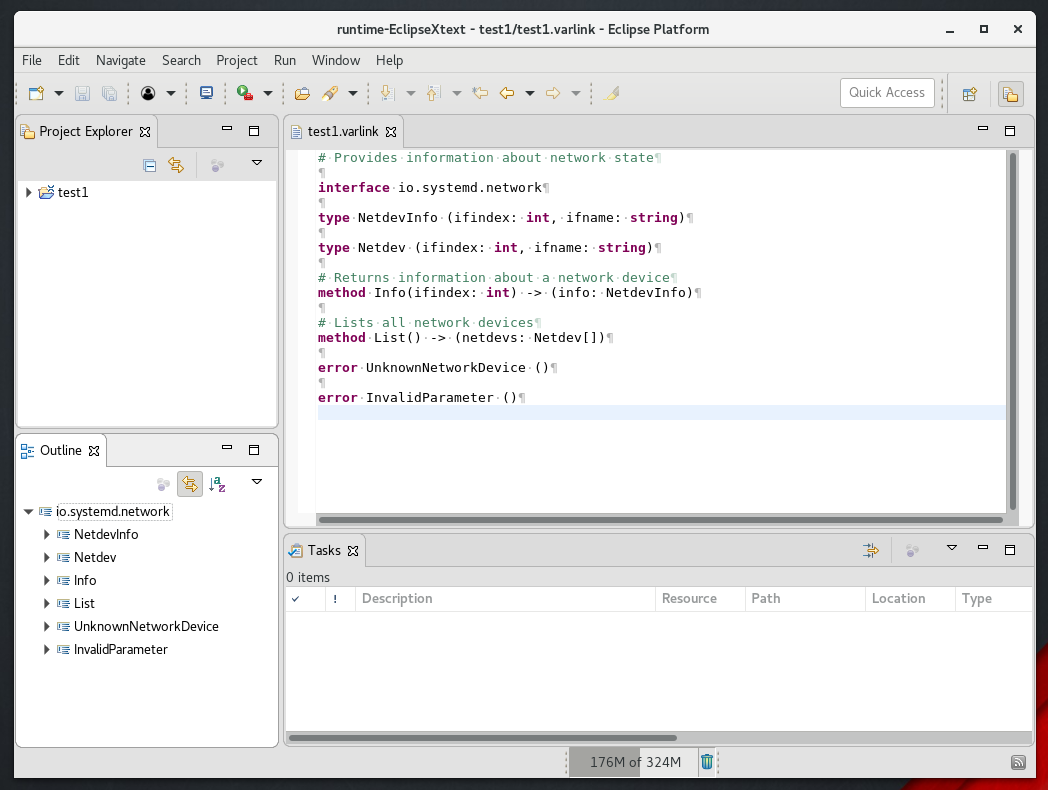

If you don’t know Xtext, it is a toolchain for creating your own DSL. Living in the Eclipse modeling ecosystem, it allows you to define your DSL grammar and it will take care of creating a parser, a complete editor with code completion, syntax highlighting, support for the language server protocol and much more. It does support the Eclipse IDE, IntelliJ and plain web. And of course you can create an Xtext grammar for the Varlink IDL quite easily. After around one hour of fighting with grammars, I came up with the following editor:

As you can see, the Varlink IDL has been parsed. I am pretty sure there are still some issues with grammar, but it is quite a good start. Now everything is available in a parsed ECore model and can be visualized or transformed with any of the Eclipse Modeling tools/libraries. Creating a quick diagram editor with Eclipse Sirius is only a few more minutes away.

What is next, what is missing

Altogether this was quite easy. Varlink indeed offers a solution for accessing system services in a simplest feasible way. So, what is next?

varlink-java is already available on GitHub. I would like to clean it up a bit, add a decent build setup and publish it on Maven Central. Adding the Xtext bits in a simple way, if possible. Tycho and plain Maven builds always tend to get in each others way.

Varlink offers something called “monitoring”. Instead of getting a single reply to a call, the call can follow up with additional updates. Like changes in the device list, following on log entries, … This is currently not supported by the varlink-java API, but it is an important feature and I really would like to add it as well.

In the current example the bindings to io.systemd.network where created manually. This is fine for a first example, but combining this with the Xtext based IDL parser it would be a simple task to create a Maven plugin which creates the binding code base on the provided varlink files on the fly.

Of course, there is so much more: creating a graphical System API browser, the whole server/interface side and dozens of bindings to create.

Conclusion

Varlink is an amazing piece of technology. And mostly because it is that simple. It does offer the right functionality to solve so many issues we currently face when accessing operating system APIs. And it definitely is a candidate to get rid of all the ugly wrapper code around command line calls and other things which are currently necessary to talk to operating system functionality. And simply using plain Java functionality (at least if you go with TCP ;-) ).

Links & stuff

- Varlink Homepage

- GitHub repository

- Harald’s post about varlink

How to install varlink (on Fedora 27, for CentOS use “yum”):

sudo dnf copr enable "@varlink/varlink"

sudo dnf install fedora-varlink

sudo systemctl enable --now org.varlink.resolver.socket

varlink help